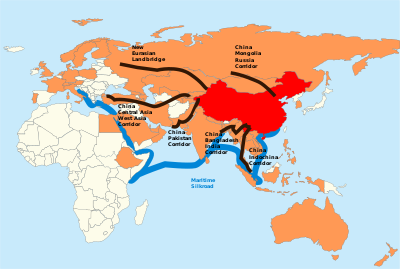

One of the biggest stories in Asian business is China’s “Belt and Road” Initiative, President Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy venture that aims to redraw global trade routes. It is estimated to cost more than $1 trillion USD, making it arguably the largest overseas investment programs ever undertaken by a single country. This could likely change the global eco-economic and geopolitical balance of power.

China is connecting itself to the world by investing billions of dollars in infrastructure projects linking some 65 countries reaching over 60 percent of the world’s population in four continents that collectively account for one-third of the global GDP, three-quarters of the global energy resources and a quarter of all goods the world moves (World Bank, 2018).

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), also known as One Belt One Road (OBOR) project, was officially launched in November 2013 but projects started years earlier are often counted. China is increasing its presence in the Indo-Pacific region—all financed and built by Chinese state-owned companies.

While the U.S. and Europe are turning inward by raising trade barriers with protectionist policies, China is aggressively moving forward with overseas investment through The Belt and Road initiative projects. The goal is to make countries easier to trade with China by positioning itself as a central player on the Eurasian and global scales.

The Chinese government calls the initiative “a bid to enhance regional connectivity and embrace a brighter future.” Some see it as a push for Chinese dominance in global affairs with a China-centered trading network.

Does the BRI-related projects make as much sense economically as it does politically?

In an article titled “Behind China’s $1 Trillion Plan to Shake Up the Economic Order,” the New York Times wrote:

Mr. Xi is aiming to use China’s wealth and industrial know-how to create a new kind of globalization that will dispense with the rules of the aging Western-dominated institutions. The goal is to refashion the global economic order, drawing countries and companies more tightly into China’s orbit… It is impossible for any foreign leader, multinational executive or international banker to ignore China’s push to remake global trade… After Mr. Trump abandoned the Trans-Pacific Partnership in January, American influence in the region is seen to be waning. (Perlez & Huang, 2017)

How much money is China spending?

While China’s BRI project is well known, there are no official details on how much money is being spent overseas on BRI-related projects. China treats its foreign investment like a state secret so the official data is not publicly available; however, there are differing estimates as to how it spends its money abroad.

“China has recently become a major financier of economic infrastructure,” according to a new report released by AidData, a development finance research lab based at the College of William & Mary. Researchers collected data from more than 15,000 sources covering 4,300 projects in 140 countries and territories to determine how much money China spent on overseas development projects between 2000 and 2014.

It took five years of painstaking research to track how money flows from China to recipient countries using online sources, like news articles, official documents in Chinese embassy websites, and aid and debt information from China’s counterparts.

Some of a brief overview of key findings:

- Chinese funds went to more than 3,485 projects in 138 countries and territories. These projects are densely concentrated in African and Asian countries.

- China provided more than $350 billion in an official loan around the world over the 15-year period from 2000 to 2014. Over the same time frame, the U.S. spent about $424.3 billion.

- African nations are the largest recipients of the aid and loans given by China since 2000.

- Over the period of 2000 to 2014, Angola and Ethiopia combined received more than $32 billion of Chinese commitments, which accounts for almost 10% of the total aid.

According to the Economist (2019), “Seven of the worldʼs ten largest container ports are in China. Overseas, Chinese companies had by 2018 helped build or expand 42 ports in 34 countries, often as part of the Belt and Road Initiative, a global infrastructure scheme. Chinese operators own majority stakes in foreign ports from Abu Dhabi to Zeebrugge” (para. 3).

The circles on the map pinpoint the location of thousands of Chinese-funded development projects. The bigger the circle, the bigger the investment. The largest circles represent projects in the multibillion-dollar range. Map by Soren Patterson, AidData/William & Mary/Screenshot by NPR

Risk-Benefit Assessment

The infrastructure investment through the BRI related projects could certainly give a long-term economic boost—many emerging market countries are lacking critical infrastructures and desperately in need of infrastructure investment and development aid. China has the financial means and expertise to bridge the “infrastructure gap.”

According to the Asian Development Bank, the emerging Asian economies will need around $1.7 trillion per year in infrastructure investment to stimulate growth (Perlez & Huang, 2017).

China’s aggressively increasing its presence in Sri Lanka and the other countries in the Indo-Pacific region has sparked a heated debate on the effect of Chinese financial investment through BRI projects.

There are also some indications that Chinese connective financing may saddle recipient governments—and their taxpayers—with unsustainable debt burdens (Hurley, Morris and Purtelance, 2018).

China Expands Its Footprint in Sri Lanka

Chinese state-owned corporation agreed to invest $1.5 billion in 2010 to build a port in Sri Lanka. After struggling to make repayments the Sri Lankan government agreed to lease the port to the same Chinese company for a 99-year in 2017 in exchange for $1.12 billion to put toward debt repayment. This has raised the concern in Chinese intention and locals fear Sri Lanka is caught in a “debt trap.”

Pakistan to Accept $6 Billion Bailout From I.M.F.

Sri Lanka isn’t the only country that has struggled to repay Chinese loans. Pakistan is deep in debt to China, and the country has to pay approximately $40 billion to China over the next 20 years just for the BRI related projects undertaken so far.

The foreign loans have now exceeded $90bn, and exports have registered a negative growth over the past five years, Dr. Abdul Hafeez Shaikh, an economic advisor to the prime minister, said on state television.

Earlier last month, Pakistan and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) reached a preliminary agreement on a $6 billion bailout package over the next three years to finance a long-running fiscal crisis. The deal, which still needs approval by the IMF board, would be the 13th bailout since the late 1980s.

“Pakistan is facing a challenging economic environment, with lackluster growth, elevated inflation, high indebtedness, and a weak external position,” Mr. Ernesto Ramirez Rigo, who led the I.M.F. mission to Pakistan, said in a press release on May 12, 2019.

The IMF forecasts Pakistan’s economic growth will slow to 2.9% this fiscal year from 5.2% in 2018.

[Update: The International Monetary Fund Executive board approved a three-year, $6 billion loan package for Pakistan to rein in mounting debts and stave off a looming balance of payments crisis, in exchange for tough austerity measures, Reuters reported on July 03, 2019 (Mackenzie, 2019)]

The Lao-Chinese railway project

As a part of the $6 billion railway project that began in 2016, Chinese workers and engineers are drilling tunnels in mountainous regions of Laos that will eventually connect eight Asian countries. Almost all the workers undertaking the Laos project are Chinese, which is estimated at 100,000 (Perlez & Huang, 2017).

China-backed Coal Projects in Serbia

In Serbia, one of the country’s largest coal-fired power stations is being expanded with the help of $715 million loans from a Chinese bank and with the work being led by one of China’s largest construction companies (Shukman, 2018).

What are the risks for countries involved?

Earlier last year, the Center for Global Development found eight more Belt and Road participant countries at serious risk of not being able to repay their loans. These affected nations—Djibouti, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, the Maldives, Mongolia, Montenegro, Pakistan, and Tajikistan—are among the poorest in their respective regions and will owe more than half of all their foreign debt to China (Kuo & Kommenda, 2018).

What does China hope to achieve?

There are growing concerns the BRI will allow China to gain leverage and political influence by exposing low income developing countries to “debt traps.” Some see it as a push for Chinese dominance in global affairs with a China-centered trading network.

On the contrary, some scholars argue that there is no evidence that China’s plan is to entrap developing countries and Sri Lanka is the only one out of all BRI projects that has ended in a 99-year lease.

AidData findings suggest that Chinese investment particularly in “connective infrastructure” produced positive economic spillovers that lead to a more equal distribution of economic activity in the localities where they are implemented. On average, a doubling of Chinese ODA produced a 0.4% increase in economic growth.

The BRI is only six years old, so its full results cannot yet be judged. However, study findings slowly begin to paint a complete picture of where Chinese aid is going and what impact it is having. The big question remains how will China protect its investment.